Bribe Outlook | Understanding the Nuances of Corruption

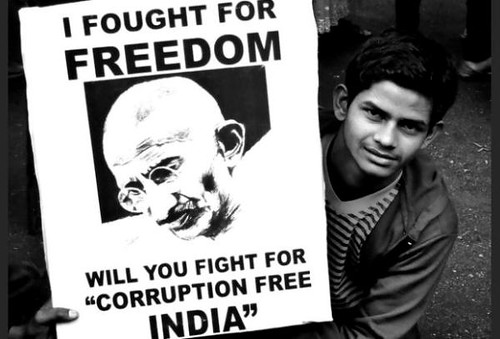

Post-independent India witnessed an emergence of institutions that formed the administrative framework. This was a period when society was getting embedded with the growing political culture and expanding economy. Corruption also emerged in a systemic manner. This article is the first installation in the four part series of analyses, exploring various factors that contributed to the growth of corruption in the pre-liberalization era.

Drain of wealth is not new to India. It was witnessed in its zenith during the colonial era. Post-independence, it emerged in a new avatar – Corruption. The literacy rate was as low as 12% on the eve of independence. Human development indices such as Infant Mortality Rate was as low as 148 soon after independence. Such reality checks forced the government to device ways to administer the emerging welfare society.

Independence ushered the beginning of a regulated economy. This period also witnessed the beginning of scams such as the Jeep Scam. In 1948, V. K. Krishna Menon, then the Indian high commissioner to Britain, had bypassed a protocol to sign a deal worth Rs.80 lakh with a foreign firm for the purchase of army jeeps. While most of the money was paid up front, just 155 jeeps landed. Though the judicial inquiry was prematurely closed, this marked the beginning of scams in independent India.

Procedures were formulated to facilitate administration. This was the main impetus of the Organisation and Methods Division that was established under the Cabinet Secretariat in 1954. Procedures were also devised to ensure transparency and accountability. However, it was abused to create ground for red tapism and favouritism due to systemic opacity created by lengthy procedures. C Rajagopalchari, the then governor general of India coined the term ‘License Raj' observing that this massive flawed system bred out of state intervention in private industries became the centre of manipulation. It was observed that around 35% of industries were rejected of licenses in 1959 thus reflecting an uncertainty that prevailed as to whether licenses were approved or not. This delayed the economic progress as well as gave immense power to the administration to decide over the issue of licenses. Thus began the era of the License Raj which ushered in a newer, deeper and more endemic level of corruption.

Moreover, with no higher vigilance authority overlooking the government’s operations, our economy became susceptible to a low growth rate. To tackle shortcomings of administrative mechanism, Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) was created in 1964. This was to primarily check corruption at the government level. However, in actuality it is a paper tiger as it is merely an advisory body. CVC lacked basic powers because it could not order or initiate an enquiry against any government representative or body. Furthermore, it was short staffed to look into issues concerning over 50 ministries.

Congress was the reigning political party during the initial decades following independence. With not many political alternatives to offer, Indian citizens were restricted in choosing one strong party among a few. Congress became the epicentre of dynasty politics and in many ways continues to be, even today. The single-party dominance might have also contributed to ensure institutional secrecy as there were not much strong opponents.

Among anti-corruption resolutions that emerged was the Prevention of Corruption Act (1988) that was the first anti-corruption law that defined a ‘public servant’, further explaining the circumstances under which a government employee can be charged of corruption? This specified that acceptance of gratification, apart from the public servants’ legal remuneration, would attract a punishment anywhere between 6 months to 5 years, including fine.

To strengthen the anti-corruption mechanism, Lok Pal bill seemingly emerged as a miracle to curb the menace of corruption at the government level. This was an ombudsman bill. Shanti Bhushan, former Law minister of India, was an initial proponent of this bill that allots adequate power to an independent watchdog that has the authority to register complaints of corruption against politicians and bureaucrats without seeking approval from the government. This brings even government servants directly under the purview of the Lokpal. However, the bill was passed in the lower house and was rejected in the upper house of the Parliament twice, once in the year 1969 and recently in the year 2011.

However noble and ingenious the idea is, the Jan Lok Pal bill is rife with weaknesses. The clauses stated are unreasonable to a great extent. For instance, the bill seeks sizable authority over Central Bureau of Investigation, so that they can direct investigating officers in corruption cases. When the executive has the primary power to direct an investigation officer, how can the Jan Lok Pal be allowed to exercise such authority?

Besides, what assurance does one have regarding the integrity of the Jan Lok Pal? The key purpose of the watch dog is to oversee the functions and transactions of government offices. Who is this authority accountable to when it faces the risk of potentially getting mired in corruption?

The recent controversy involving P J Thomas, the former Central Vigilance Commissioner who quit following allegations of corruption is a landmark example of how the integrity at such a level can be compromised.

Its impact is superficial and limited with its primary focus lying only on political corruption. Who follows and acts against retail or petty corruption? Its biggest misconception is that only government officials indulge in corruption. It fails to penetrate deeper into the system of corruption that is becoming pervasive over the years. Graft committed by civil society members does not come under the purview of the bill.

Corruption cannot be attributed to one aspect or any single institution but to multiple factors. Increasing population along depleting resource base has provided a moral justification to corruption to thrive in all its length and breadth. Finding a fast acceptance in our political culture, this confronts us with newer versions and deeper effects. The post-liberalization period witnessed high scale of corruption that was backed by advanced technology and integrated global economy.

--Juwairia Mekhri